We were driving to run field tests with young mothers in the remote villages of Netrang in Gujarat, India. Netrang, like much of rural India, has been struggling against the scourge of malnutrition. Despite India’s 50% increase in GDP since 1991, more than one third of the world’s malnourished children live in India. Mothers give birth to malnourished children who end up dying from famine or give birth at a young age to more malnourished children. This is a self-reinforcing cycle that causes malnutrition to persist.

In the backseat, we had prototypes made of cardboard, pipe cleaners, construction paper, and straws. These odd-looking objects had been constructed in a couple of hours, and could have been mistaken for the remnants of an afternoon arts and crafts class with a group of 5th graders.

How could such a complex, deep rooted, critical challenge be addressed with such a seemingly simple approach and only a few days worth of work? What exactly were we doing? How could these colorful, ad hoc artifacts help break generations of poverty?

Finding Solutions for Malnutrition

The drive to Netrang was part of a five-day workshop on human-centered design. Staff from the Aga Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP) and Aga Khan Foundation (AKF) came together to find innovative ways to explore and come up with solutions for malnutrition, one of the most severe challenges facing India today.

The intrinsic goals for the workshop were to (1) introduce participants to the human-centered design process and (2) prepare them to run their own design process for their own specific challenges. This is done most effectively through a live design challenge, framed as an open-ended question: How might we create greater awareness, access, and use of best practices in nutrition for young mothers and their children?

“Although the workshop in India was framed around the challenge of malnutrition, the main goals of the workshop was to bring awareness and understanding of the design process itself.”

During the drive to the field, Jairam, one of our workshop participants, asked, “What exactly is human-centered design (HCD)? Aren’t all products and services designed for people?” For a few seconds, I paused and reflected on this insightful and practical question.

Human-Centered Design

The term human-centered design (HCD) was coined by Don Norman, the Vice President of the Advanced Technology group at Apple in 1990s. Although a new term and concept for the world, HCD draws from the expertise of many traditional and well developed and diverse professions including anthropology, psychiatry, investigation, architecture, engineering, and storytelling. HCD is a thoughtful process that brings together a diverse team and gives them a methodology to navigate complex problems to create change.

Innovation by design is not just reserved for large tech companies building new software. The same principles can be applied to address challenges in the international development and humanitarian space. The beauty of the design process lies in its versatility.

“The design process doesn’t guarantee success but it certainly adds to our ability to navigate the complexity of the challenge, helps us identify what matters most for the people we are serving and significantly increases our chances of creating solutions that can effectively have impact in their lives.”

Munir Ahmad, Global Lead for Innovation, AKF.

It was integral to remind ourselves at this stage that the “alchemy” of HCD was not in these artifacts, but the very process which brings together a diverse group of experts and gives them a methodology for navigating through an uncomfortable and seemingly insurmountable complexity.

The workshop took place in a “no frills” campus with bucket showers and snake warnings. Yet, the space was more like a sanctuary. Fashioned with sustainable architecture, exotic birds, aromatic flowers, lush gardens, and vegetarian food that made you forget about meat (if you haven’t done that already). With only one building that had WiFi, this oasis undoubtedly brought the participants closer together as they bonded throughout the week. Aside from the intense design workshop, there was not much else to do except tell stories (something that they were unsurprisingly good at). Design teams work exceptionally well together when they are able to feel comfortable, have psychological safety to speak their mind, and the mutual respect to listen to their teammates. They thrive off flat hierarchies and those who are often marginalized are given a voice in a process that really democratizes decision making.

Design Teams thrive off flat hierarchies and those who are often marginalized are given a voice in a process that really democratizes decision making.

Read on to hear about the roles our workshop participants played as they walked through the design process.

The Researcher and Psychiatrist

In a typical design process, the first step is called the Understand phase. In this phase teams conduct expert interviews and desk research to understand the challenge and map what they know already and what they are curious to learn. Due to the time constraints of the workshop, during the first day participants were taken through a quick orientation of the overall design process and the challenge. A local representative was brought in to explain the challenge and presented insights from expert interviews and desk research, and scoped the challenge of malnutrition for the group. This saves a lot of time. The second day is really where participants get their feet wet and it is the part of the process that separates the design process from many other approaches.

We are focused on trying to understand the underlying or implicit needs, challenges, and aspirations that are often not well understood.

For our challenge, interview questions included: What are the priorities for your child’s needs? What does nutrition mean to you? Why is this the priority for your child?

The design research interview is a method that requires a skillset that may be one of the hardest to learn in the design process. However, it is a skill that can be coached and improved over time. The following are useful reminders for conducting a good design interview:

- Searching for aspirations and motivations

- Staying curious

- Try and have a conversation

- Look for stories

- Creating a safe space

- Bring out emotions

- Ask open ended questions

- Ask questions that start with “why”

The Investigator

After the Empathy stage is over, it is time to begin digesting what has been learned through the Synthesis stage. During the last stage, we received a lot of information, and while some information may be helpful, most of the information is likely not very relevant.

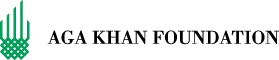

Synthesis begins with each group member recounting the highlights of the interview by attempting to tell a story from their notes. While this is happening, the remaining group members are writing down what they find most interesting. We are looking for nuggets of information that are surprising, telling or that have some tension or contradiction embedded within them. These nuggets will make us say “that was interesting” or “that was unexpected” or “that was bizarre.” If most of the team isn’t saying this about a particular piece of information, then it probably isn’t what we are looking for. From here, the teams select around 5 observations to take to the next stage.

The participants in India noted the following interesting insights:

- Children were eating packaged, processed foods (chips, biscuits, etc.) for main meals despite the availability of nutritious foods and locally grown crops

- Premixes and iron pills that reduce malnutrition were widely available yet not taken by children

- Mothers were not aware of their own children’s health conditions and that they were underweight and malnourished

- There was a lack of awareness of the benefits and resources of Anganwadi centres. Anganwadi centre is a space in the village that provides multiple services to women, children up to 6 years and adolescent girls, ranging from supplementary nutrition, pre-school education, nutrition education, health check-ups, immunization, and referral services

- Anganwadi workers focused more on the severely malnourished, thus neglecting the easily preventable cases

Each team had many compelling observations, but they could only select one to bring forward. This is an important part of the design process where the larger challenge is scoped down into a smaller, more manageable challenge that may be the most critical, or could possibly lead to the greatest impact. Other challenges may be addressed in separate or subsequent design sprints.

The last part of the Synthesis stage is when the chosen observation is turned into a Point of View (POV) and then a How Might We (HMW) question. Here are examples of a POV and HMW that one team came up with:

We met two mothers and adolescent girls accessing services from Angarwari centers. We were struck by the fact that available products like premix and iron pills are taken but not consumed by mothers and adolescents. We wonder if this means that products are distributed without taking into account the needs, cultural habits and feedback from beneficiaries. We see an opportunity to create ways to improve beneficiary adoption of recommended products.

After having decided on their POV, the team brainstormed several HMW questions that could lead to a well scoped solution space. After lots of discussion, the team decided to move forward with:

HMW motivate young mothers to adopt healthy behaviours by providing more accessible information about nutrition?

When creating the POV and HMW, it is important to remember:

- There are no right answers

- Don’t be afraid to take a leap of faith

- Keep brainstorming POVs and HMWs until you feel it is right

- Ensure they are neither too broad nor too specific

The Architect and Builder

After Synthesis, teams entered the creative phase of Ideation. Collectively, they came up with many ideas for solutions. If the ideas are not free flowing or relevant, it is common to go back to the last stage and rephrase the HMW question. Remember the following tips during ideation:

- Ideas should be diverse (products, services, physical, digital, etc.)

- Everyone should contribute to the ideation process

- Use a headline that readily describes what the idea is

- Draw a quick doodle to go with the idea

- Avoid criticism and just get the idea up on the wall

Once ideas are out there and the team feels like they have enough (about 50 or so is a good number). They should select one to two ideas to move forward with. Teams can narrow down the ideas through voting, categorizing, or using criteria to eliminate ideas. Categorizing and identifying design criteria is about understanding what the team values collectively. Key criteria should be brainstormed in the group such as cost, sustainability, ease of implementation, impact, accessibility, uniqueness, etc.

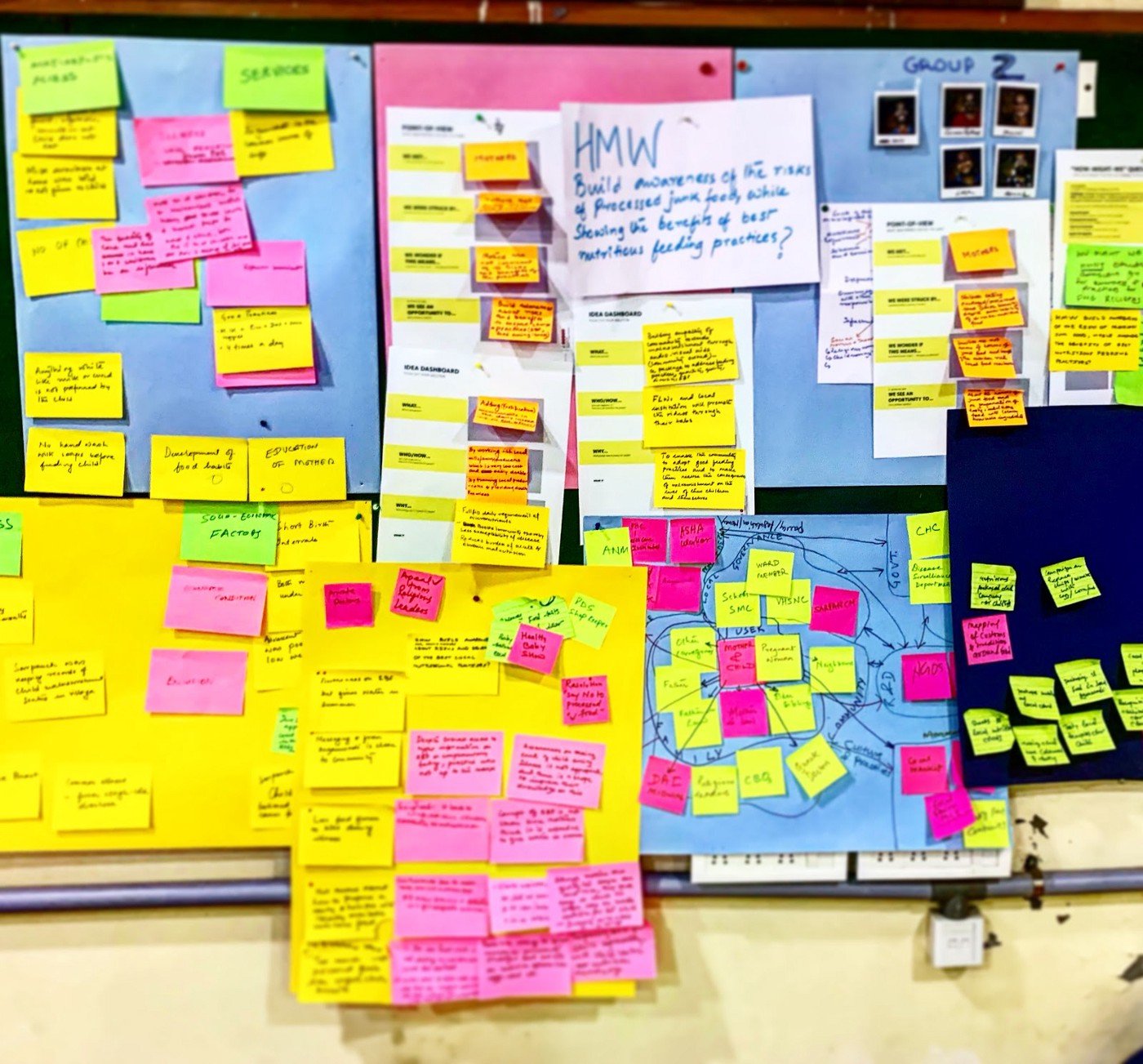

Our workshop developed both creative and diverse ideas, including:

- Fortifying nutrients in the local village mill

- A device that shows if your child is malnourished

- A video or skit created by the community showing best nutrition practices

- A kitchen garden

- A plate that helps you remember food groups

From here, it is time to further develop the ideas into Idea Dashboards and Storyboards. An Idea Dashboard gives you the 30,000 foot view of an idea. The key components include:

- What is the solution?

- Who will implement it and how will it be implemented?

- Why is it important?

The next level of fidelity of an Idea Dashboard is the Storyboard. A Storyboard is like a comic strip that highlights 4–5 of the key events in the process.

There are several steps in the design process that are strategically broken into smaller pieces in order to keep the process moving, manageable and ensure the team is aligned.

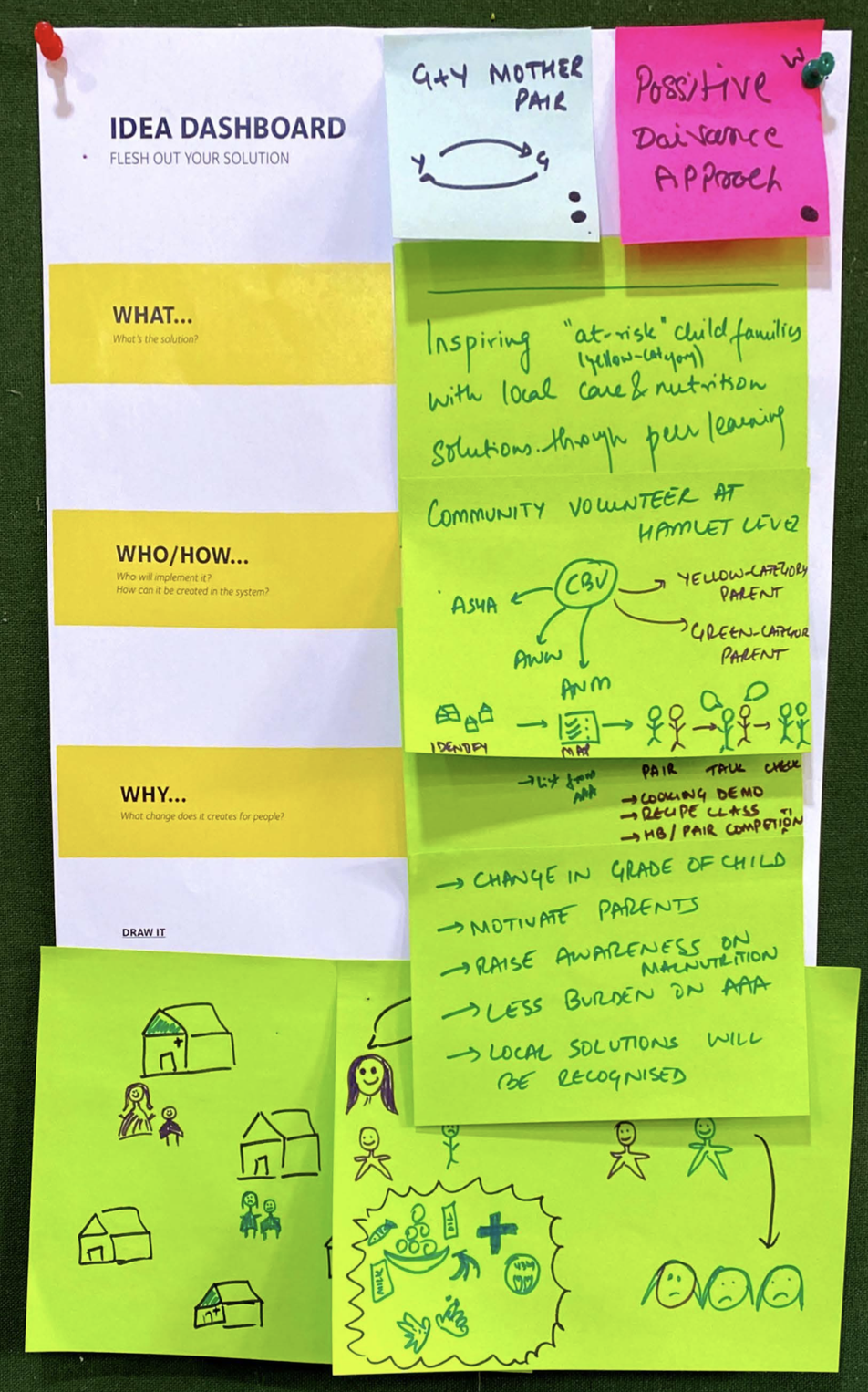

The Engineer and Scientist

After Ideation, it is time for Prototyping, where participants build something to test their idea with the target audience. The important thing to remember is that we are only building to test assumptions. So first we must brainstorm a list of assumptions that we are making about their idea. Often we live in a bubble thinking our ideas are great or that everyone has the same perspective. This is not only wrong, but is extremely dangerous. Scaling an untested idea to a target group can lead to detrimental effects on the community and deplete valuable resources. Once you have your most important assumptions, build something to test them.

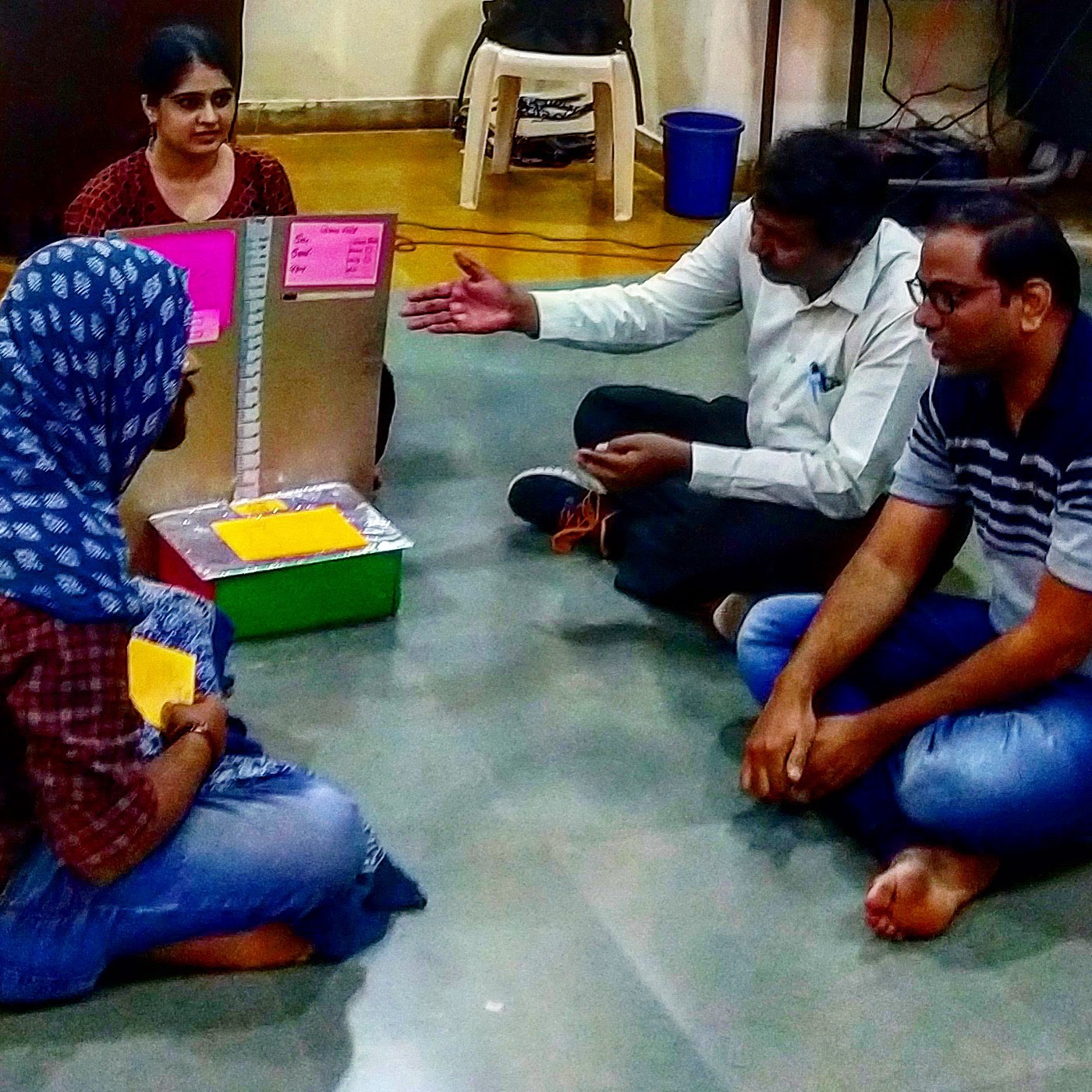

One of the teams chose to create a prototype of a device that would show young mothers if their child was malnourished. We wanted to make sure the device was actually understood by the target audience, so the team listed their assumptions that the mothers would understand what the device is by looking at it, and the information it provided about the child. They could then design and build the device and information that it was providing with the audience in mind. The prototype does not have to be an elaborate or a high-fidelity device; it only needs to be developed enough to test the assumptions. This didn’t take more than 2 hours to make.

It became clear again why these cardboard artifacts were sitting in the backseat on our drive to Netrang. They were mini-experiments in a very well thought out process. In a highly efficient way, these productions were constructed to test one or two key assumptions. If they could either prove or disprove a question, they were highly useful. They would tell us if we were onto something or if we were completely wrong.

If we were wrong, we would need to return to some earlier phase of the process. Did we ask the right questions during Empathy? Did we choose the right observation, the right insight, or the right HMW question during Synthesis? Should we go back and select another idea to test? Did we build the idea well enough to test or choose the right assumption to test? In this way, the process is forgiving as the team finds the most critical problem to tackle and a validated solution to that problem.

If we were onto something and our target audience validated our assumption(s), we can go back and test another assumption further down our Idea Storyboard, do more testing, or slightly improve our current prototype. Each iteration of the prototype gains greater granularity as we reach an effective solution that is ready to pilot, where a larger investment is made to test the prototype with a wider audience. After the pilot, the concept may be ready to scale. The key to building a solution this way is efficiency and efficacy. Over time, these prototypes could be developed, combined, and turned into real products or services or applications. They may eventually become their own entirely new systems, organizations, or enterprises.

The Storyteller

The last day of the workshop is called Storytelling, where participants showcase their process and prototypes. The presentations allow for a deep discussion around the core challenges and provoke further questions to address in the next stages of the design process. Teams articulate who they solved the challenge for, what the core challenge was, what their solution was, what they tested, and what they learned. They also discuss what their next steps are. Typically, they receive feedback from an expert panel, other teams, or other stakeholders.

This light-hearted and engaging stage is critical to understanding exactly what the participants learned and the process they went through. It is important to keep these key tips in mind for presentations:

- Keep it simple and concise

- Act out a performance to engage the audience

- Go over only the key highlights

The most compelling presentations touch the emotions of the audience while keeping things simple. A simple message can be memorable and actionable.

After a few moments of reflection, I was ready to answer Jairam’s question. Designers are those who imagine and develop new products or services based on human aspirations or needs. Many of us consider ourselves as designers solving real and important challenges. However, the reality is that we live and work in complex systems. Organizations do not always allow us to truly understand the aspiration and needs of our target audiences, nor do we have the space, resources, process, and time to test and develop solutions that address these very needs with efficacy. How often are we checking off boxes, reporting to upper management on numbers that are likely irrelevant, iterating existing documents or templates or tweaking designs only marginally? How often do we see the entire process of a product or service being delivered from the initial need finding to the distribution of a well designed and tested solution in the well oiled machine of a large company or organization? All of this leads to products and services that are being created each day that lack deep understanding, reflection, rigorous feedback, and most importantly desirability from the people we design for. We fail to create products and services that are truly meaningful and sustainable for our target audience and we don’t address the many complex challenges that actually exist in people’s lives.

The reality is that we live and work in complex systems and organizations that do not always allow us to truly understand the aspiration and needs of our target audiences. Nor do we have the space, resources, process, and time to test and develop solutions that address these very needs with efficacy.

Human-centered design is a process that brings back the full cycle of design and development into the hands of a diverse team empowered to solve a complex challenge. Along with the process, the team must not only have adequate resources (time and budget) but more importantly they must care deeply about their challenge. Upon leaving this five-day workshop, participants feel equipped with a super power that allows them to creatively and effectively navigate their way through the incredibly complex social challenges they so humbly seek to address.

Originally written by Saad Rajan for Accelerate Impact. Accelerate Impact is a global initiative from the Aga Khan Foundation that sparks the co-creation of innovative solutions with communities to increase our collective impact.