Last month, the Aga Khan Foundation (UK) hosted a group of over 200 people dedicated to advancing girls’ education. Brought together over two days, the global audience and participants featured government ministers, international institutions, foundations, academics, international NGOs, and local organisations to share insights, challenges and lessons learned implementing a large-scale education programme in a high-risk environment.

The event marked eight-years of implementation of Steps Toward Afghan Girls Education Success (STAGES), funded under the Girls Education Challenge by the UK’s Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and, more recently, by USAID. It featured keynote speeches from Alicia Herbert OBE, Director for Education, Gender and Equality at FCDO and UK Gender Envoy and from Her Excellency Rangina Hamidi, the Acting Afghan Minister of Education. The opening address was given by Dr Matt Reed, Global Director of Institutional Partnerships at AKF and CEO of AKF UK. This blog has been adapted from his remarks.

It is my distinct privilege to host this group today to discuss one of the issues our organisation feels most strongly about: how to help girls learn better, live better, and thrive – how to help them fulfil their potential and create (or seize) new opportunities. In short, how to help them have better futures.

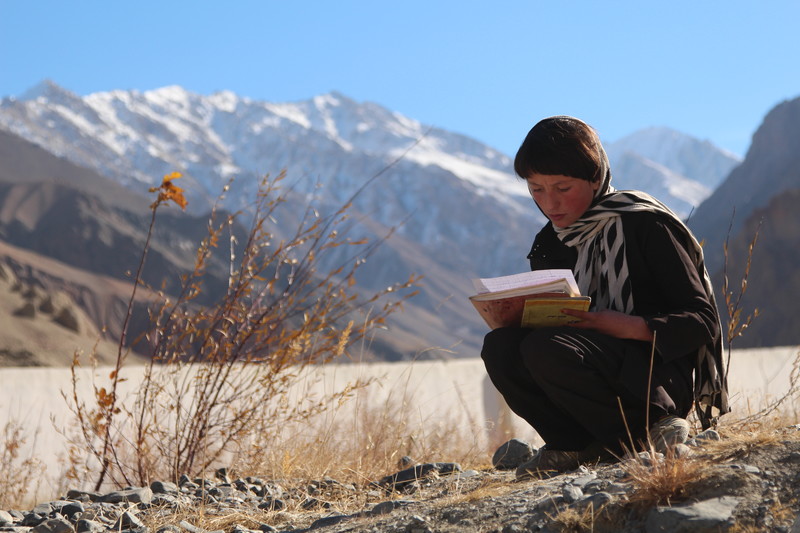

This commitment has been fundamental to the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN) for over a century. Among the very first institutions of what is now known as AKDN were schools in Gujarat and Tanzania, intended to help girls get an education, to improve their prospects and the prospects of their future families. In the last three decades alone, AKDN agencies have directly helped over 10 million girls get into school, stay in school, and learn in school.

Today, we continue to live this legacy through our work in 15 countries. Marginalised children and youth – especially girls – are at the centre of the Aga Khan Foundation’s education strategy.

To help them, we focus on a few broad areas:

- First and foremost: improving access, but also critically, quality;

- Secondly: making sure that their education is locally relevant and rooted – and that they are supported by their entire communities;

- Thirdly: promoting pluralism by ensuring that classrooms are inclusive; and lastly

- To achieve these things, we have to make sure that teachers are trained and supported, so we focus especially on their needs.

We are implementing this work in a variety of ways. One example draws on lessons we have learned from STAGES and seeks to apply them across multiple countries. It is called Schools2030.

Schools2030 is a coalition of nine foundations, led by AKF, that will be working over ten years in ten countries in 1,000 schools, with the mandate of finding locally-led solutions to improve learning outcomes and work towards SDG4 – quality education for all. Much of the rationale and approach behind Schools2030 was informed by lessons learned during the STAGES project – the aim is to root global resources in local realities about what works to help girls and boys learn against the odds. That phrase – learn against the odds – encapsulates what we have been trying to do with girls in Afghanistan, and indeed, what this conference is all about today.

So as we think today about STAGES, we note that it has been a flagship programme for us, building on AKF’s history of promoting girls education in India, Pakistan and the region since the 1980s, and on AKF’s own previous work in Afghanistan since the mid-1990s, which was supported by Canada, Switzerland, and others, as well as with our own resources.

For almost a decade, the UK has been rallying the world on the issue of girls education, galvanising international attention on this fundamental issue and catalysing significant investment, attention, and action globally. We must recognise and applaud its leadership and achievements.

And so, since 2013, through the path-breaking leadership of FCDO, and with support from the fund manager PriceWaterhouse Coopers, we have been implementing the STAGES project together in Afghanistan, leading and learning from the extraordinary consortium that you will hear from today. So I want to thank all of our outstanding partners in this work, implementing alongside us and bringing our collective expertise to bear on the challenge of promoting girls education in one of the world’s most difficult contexts.

Please join me in recognising the work of Care, Catholic Relief Services, Save the Children, the Afghan Education Production Organisation, the Aga Khan Education Services, Roshan Telecommunications, and of course my colleagues at AKF Afghanistan.

“A girl that started this programme in 2013 is now on the verge of graduation – a generation of girls have literally grown up with us.”

The results have been impressive: 210,000 girls have benefitted in 14 provinces, three-quarters of the country. That means that a girl that started this programme in 2013 is now on the verge of graduation. That is a generation of girls who have literally grown up with us.

Along the way, we have supported or established 1,700 community-based education centres, trained 7,600 teachers, and helped almost 2,000 older girls become teachers themselves. They have also become role models in the process, showing what is possible for girls who go to school and stick with it.

Equally important, our consortia has worked with over 7,000 mullahs or shura members to ensure that communities support these girls and their schools.

What has this accomplished?

- Girls’ enrolment has increased from 30 percent to 52 percent;

- Graduation rates have doubled (to 30 percent);

- Attendance is 93 percent – 30 percent higher than other schools;

- 80 percent are staying in school;

- Learning levels are consistently higher among girls in these schools.

We have to be cautious, but the evidence suggests that some of these changes will be lasting.

We know that communities are committed: they have donated over 59,000 hours to ensuring that girls can go to schools. During Afghanistan’s COVID-19 lockdown, our rapid evaluation showed that 99 percent of girls were still able to study, even while coping with disruption and more household responsibilities. 70 percent had assistance from their local shuras, showing strong community support.

This gives you a sense of how social norms have shifted during these last eight years. That won’t go away overnight.

Those last findings are crucial, in my view, because they touch on two of the biggest challenges – the biggest questions – for the future of girls’ education in Afghanistan right now.

The first challenge is getting these girls back in school after the pandemic lockdowns. We know that in many other parts of the country, many girls were not as fortunate as those we have worked with and many will not come back, if they were ever allowed to enrol at all. So the challenge now is to double or triple our efforts to overcome that pandemic inertia – with so much to overcome already. We need a national – and indeed a global – emergency effort to get kids back to school, especially girls.

The second looming challenge is the very issue of Afghanistan’s future: if the peace process is successful, as we all pray it will be, what would happen to girls’ education in a Taliban-linked government?

“Our experience shows that change – indeed, progress – on girls’ education is possible in even the most conservative communities.”

Our experience shows that change – indeed, progress – on girls’ education is possible in even the most conservative communities. With the right kind of engagement – focused on addressing and removing the practical obstacles and challenges to girls’ participation – we can make a difference. We have shown that.

ODI’s recent report on education and the Taliban supports this insight. It shows very clearly that there is not one Taliban, but many, in dialogue with communities and leaders wherever they are present, creating varying levels of acceptance for girls in school and highlighting how communities themselves can push for accommodation when it is a priority. And even the Taliban realises the value of education – pockets of it accept that Afghanistan has changed and needs new skills for a new era. As ODI points out, because the Afghan education budget is so dependent on donor support, the international community should use that leverage for influence in the discussion over the future of education.

Surely our work together under STAGES shows the value of staying engaged, and staying invested. It should give us confidence that it is worthwhile, but also help convince us that engagement must be maintained. We owe it to the generation of girls who have grown up with us these past eight years – and to all the others who have not yet had the chance.

During today’s conference, we want to think about the lessons the STAGES experience holds for the future – not only in Afghanistan, but in other fragile contexts. What have we learned that might be relevant elsewhere? And what questions still need answers – and action?

Yesterday, over 120 experts gathered to help chart those lessons – from Asia, Africa, Europe, and North America, representing governments, international organisations, foundations, academia, international NGOs and – vitally – local organisations. Having the voices of people from these schools and communities greatly enriched the discussion and brought perspectives that aren’t always represented in meetings like this.

“Understanding local context, consulting communities in design, and empowering them to act is fundamental.”

There were six concurrent workshops covering different topics – Gender Transformation, Re-working cultural norms, Sustainability, Innovation, Engaging boys and men, and Safeguarding. Here are a few of the headlines from those conversations, which I suspect we will also hear reflected today:

- Long-lasting change requires more than working in the classroom – community and families play a crucial role.

- Extra-curricular activities build girls’ self-confidence and self-respect, and help bond peer groups of girls together to support each other.

- Pathways to work – including teaching – builds ambition, gives girls credibility and standing in their families, and creates the female role models that so many girls lack.

- Programmes must address the enabling environment for access and retention: girls need to know their rights – to education, as well as how they should be treated. Tools to address the practical barriers like toilets, transportation, and fees are essential.

- Sustainability has to be thought about from the design phase, but flexibility in fragile environments is crucial as circumstances change and needs evolve.

- To achieve generational change, the approach and investment has to be long-term; it has to engage government to embed changes into the system; it must support and transform teachers and teaching. And it should institutionalise safeguarding: to gain a society’s faith in education, every child must feel safe in school, and every parent must be confident that their children are safe there.

- Understanding local context, consulting communities in design, and empowering them to act is fundamental.

That is already a full list, but barely scratches the surface of what my colleagues tell me was a very rich set of discussions. We are looking forward to picking up some of these threads in today’s conversation – and to continuing them, and our work together, in the months and years ahead.

Thank you again for coming – and thank you for everything that each of you is doing for girls and their futures.